TNR (Trap-Neuter-Release) Explained

A recent inquiry has prompted us to address a critical concern.

Feral cats pose a significant threat to the environment and wild bird populations; why support the protection of an invasive species???

By promoting TNR we are, in reality, working to protect the environment.

Although this may seem contradictory, the ultimate goal of TNR is to eventually eliminate outdoor cats or reduce their population to a minimum.

It is vital to recognize that all cats adopted through TNR programs are placed in indoor-only homes (unless specified as barn placements), directly reducing the number of outdoor cats and thus benefiting affected native species. The remaining cats are sterilized and returned as community cats, thereby successfully limiting population growth that would have otherwise gone unchecked.

These community cats are cared for by Colony Mangers who ensure they are fed. This means that they are not driven to hunt as hungry cats are driven to hunt, and again benefits our native species.

This process requires time; however, it is essential to acknowledge that TNR advocates and participants are playing a crucial role in minimizing the number of outdoor cats.

There is not a current legal solution other than TNR. So despite any opposing opinions, TNR leaders, Colony Mangers, and veterinarians are the only ones who are directly addressing this issue.

If you oppose this practice, we recommend sitting back and watching the work speak for itself. There are currently no available or active cat removal or euthanasia services. In the absence of trusted TNR programs- your problem will drastically worsen.

To safeguard your community and environment, learn how you can contribute to TNR efforts.

-Alanea N Fullerton B.S., M.P.S

Master Biologist in Wildlife Management

Director, Whiskers In The Wild

Facts about Community Cats

The science behind why community cats are safe members of our communities

Data-backed publications supporting community cats pose no health risks to the public

Courtesy of Alley Cat Allies

Science shows community cat colonies aren’t a risk to humans

Public health policies all over the country reflect the scientific evidence: community cats live healthy lives outdoors and don’t spread disease to people. But advocates of catch and kill programs continue to justify this cruel practice by insisting that community cats represent a threat to public health and that they do spread disease. “There’s simply no evidence to back up these claims,” says Deborah L. Ackerman, M.S., Ph.D., an adjunct associate professor of epidemiology at the UCLA School of Public Health.

More and more, public health officials are embracing Trap-Neuter-Return (TNR) for community cats and replacing outdated policies based on unfounded fears.

The health risks that catch and kill advocates most often blame on cats are intestinal parasites, rabies, flea-borne typhus, and toxoplasmosis. Yet the spread of these diseases has never been conclusively linked to community cats.

Parasites are species-specific

Most diseases that infect cats can only be spread from cat to cat, not from cat to human. You are much more likely to catch an infectious disease from the person standing in line with you at the grocery store than from a cat.1 In fact, a 2002 review of cat-associated diseases published in the Archives of Internal Medicine concluded that, “cats should not be thought of as vectors for disease transmission.”2

Infectious diseases can only spread from cats to humans via direct contact with either the cat or its feces, and feral cats typically avoid humans. Statistics from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) show that cats are rarely a source of disease, and that it is unlikely for anyone to get sick from touching or owning a cat.3 “Feral cats pose even less risk to public health than pet cats because they have minimal human contact, and any contact that does occur is almost always initiated by the person,” says Ackerman

Ackerman says that the risk of catching an intestinal parasite like Cryptosporidium and Giardia from cats has been vastly over-hyped. Molecular studies show that these parasites are usually species specific, meaning that the type that infects cats does not infect humans, and “some studies even suggest that cats and other animals are more likely to catch these parasites from humans than vice-versa,” according to Ackerman.

No danger from rabies

The notion that stray cats spread rabies is another empty argument used by advocates of catch and kill programs, says Ackerman. The last confirmed cat-to-human transmission of rabies occurred in 1975. The risk of catching rabies from a community cat is almost non-existent. Statistics from the CDC show that as a source of rabies infections, cats rank way behind wild animals like bats, skunks, and foxes who account for more than 90 percent of reported cases of the disease.4

Trap-Neuter-Return is a safeguard against rabies, because “the vaccination component of TNR programs ensures that the cats in managed colonies cannot catch or spread rabies,” says Ackerman.

Even in the unlikely event that a community cat develops rabies, it can’t spread the disease to people without biting them, and community cats rarely seek direct contact with humans. The idea that cats will unexpectedly jump out of alleys and bite children is just as ridiculous as it sounds. A 1998 analysis showed that about 90 percent of cat bites were provoked, and the vast majority of cat bites are caused by pets.5

Since Atlantic City, New Jersey began its TNR program in 2001, the city hasn’t had a single complaint about community cat bites or scratches. Learn more about how community cats do not spread rabies.

Flea-borne typhus is rare and cats don’t play a part in the fleas arrival or growth

Flea-borne typhus is another infectious disease sometimes erroneously blamed on community cats. The disease is caused by Rickettsia bacteria that infect fleas, and most U.S. cases occur in Texas, Hawaii, and California. Although infected fleas may hitch a ride on community cats, the chance of becoming infected with flea-borne typhus via a community cat is extremely low. Ackerman says, “flea-borne typhus is rare even in areas such as Southern California, where the disease is endemic.” For instance, in 2009, Orange County, California reported 12 cases of flea-borne typhus out of a population of 3 million residents6, making the chance of infection just 1 in 250,000, about the same as the risk of being hit by an asteroid.7

Removing cats does not halt the spread of flea-borne typhus, because cats don’t spread the disease: the fleas themselves do. Cats are merely a host for fleas and if the cats are eliminated, the fleas simply find another host like squirrels and raccoons. “Fleas are very versatile. They live on cats, dogs, opossums, rats, and mice,” Ackerman says.

For this reason, public health officials in Texas, where flea-borne typhus is endemic, have focused their efforts on controlling fleas rather than their hosts. Outbreaks are rarely traced to cats. In 2008, the CDC and Texas health authorities examining a cluster of flea-borne typhus in Austin found the Rickettsia bacteria in only 18 percent of cats, as compared to 44 percent of dogs and 71 percent of opossums, near the homes of people infected with the disease.8

Most cases of toxoplasmosis stem from undercooked food, not cats

Catch and kill advocates argue that community cats transmit toxoplasmosis, a parasitic disease that spreads via Toxoplasma oocysts shed in the feces of an infected animal. But studies show that the overwhelming majority of toxoplasmosis cases actually result from eating undercooked meat. According to CDC statistics, toxoplasmosis is the third leading cause of food-borne illness-related death in the U.S.9

Pregnant women and their fetuses face a higher risk from the disease, a fact that catch and kill advocates often abuse to incite public paranoia. But a study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine in 2002 concluded that pregnant women were unlikely to catch toxoplasmosis from a cat.10

It’s rare for anyone to catch toxoplasmosis from a household pet (cats are not the only carriers; dogs, birds, and other mammals can also carry the parasite), let alone a community cat with whom they have no contact. Even if a cat is infected with Toxoplasma, it typically only sheds the disease-spreading oocysts for a few weeks. To catch an infection, a person would need to have direct contact with these infected feces. Most people go out of their way to avoid touching the contents of their pet cat’s litter box, and they’re even less likely to touch community cat feces. In other words, even if a community cat leaves feces in your garden, you would need to touch it and then somehow ingest the feces to get toxoplasmosis.

Colony caregivers are as healthy as everyone else

Maybe the best proof that community cats are not a health risk is that community cat caregivers are healthy. “If community cats transmitted disease to humans,” says Ackerman, “colony caregivers, who spend more time around community cats than most people, would experience a heightened rate of disease, and this simply isn’t the case.” None of the many caregivers she’s interviewed have ever reported becoming sick from their work with community cats. No study has ever shown that colony caregivers have any increased risk of disease, despite their regular contact with community colonies.

Catch and kill doesn’t improve public health

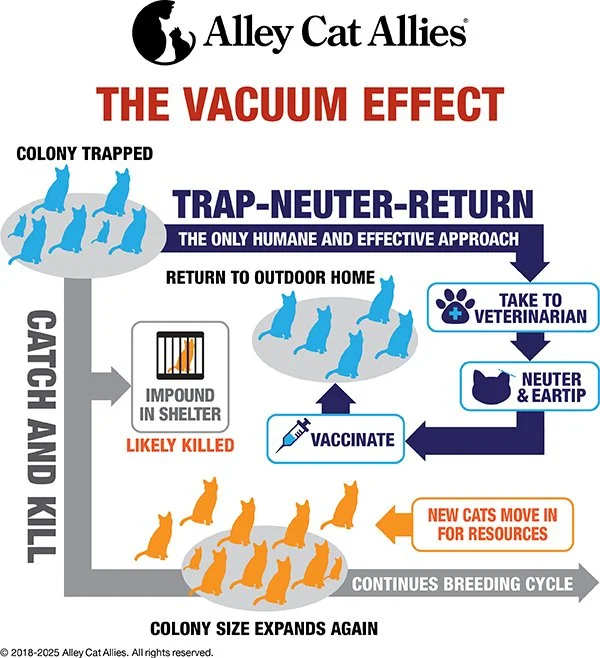

“Catch and kill policies are fear-based and rely on old wives’ tales and flawed research to justify prejudice against cats,” says Ackerman. Removing community cats is not a sustainable solution, because that only opens up new territory for other community cats to use. Learn more about this vacuum effect. According to Ackerman, there’s absolutely no evidence that catch and kill policies reduce the incidence of human disease.

Trap-Neuter-Return programs protect public health and prevent the spread of disease

Trap-Neuter-Return programs stabilize community cat populations, and the vaccination component ensures that cats are protected against disease. These programs also allow cat caregivers and public health officials to monitor the health of cats and ensure that they’re immunized, and that “protects the health of cats and humans alike,” says Cash.

Catch and kill programs offer no such benefits,because cats are simply removed without regard to their health.

“TNR is good public health policy,” says Cash. Atlantic City has been collaborating with Alley Cat Allies since 2001 to manage community cat colonies under the city’s famous boardwalk. The TNR program that Atlantic City developed with Alley Cat Allies has never posed any health problems to the community, says Cash.

“Before our relationship with Alley Cat Allies, I was getting numerous complaints about feral cats,” he said. But since Alley Cat Allies began managing these colonies with TNR, the problems have ceased entirely. “The [cat] population that’s here is much healthier,” says Cash. “They’re coexisting with people very well now. Most people don’t even know the cats are there.”

While catch and kill advocates cling to outdated thinking and hyped-up stories, the people studying, teaching, and defending public health recognize that community cats do not spread disease to people. Policies based on fear, hype, and hysteria serve neither the public nor the cats, and will only end in more cats being killed.

Instead, community cat policies should reflect the science and the facts: community cats are healthy animals. From a public health standpoint as well as a humane one, the best approach for community cats is Trap-Neuter-Return because it benefits the cats and the community.

American Association of Feline Practitioners and the Cornell Feline Health Center, Cornell University, College of Veterinary Medicine. Zoonotic Disease: What Can I Catch From My Cat? 2002.

Kravetz, Jeffrey D., and Daniel G. Federman. “Cat-Associated Zoonoses.” Arch. Intern Med 162, no. 17 (2002): 1945-1952.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diseases from Cats. July 28, 2010.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Rabies – Epidemiology. September 18, 2007.

Patrick, G.R., and KM O’Rourke. “Dog and Cat Bites: Epidemiologic Analyses Suggest Different Prevention Strategies.” Public Health Report, 1998: 252-257.

Notifiable Diseases in Animals: Joint Meeting of the CCLHO Communicable Disease Control and Environmental Health Committees, April 15 (2010) (written statement of Deborah L. Ackerman, M.S., Ph.D., Adjunct Associate Professor of Epidemiology, UCLA School of Public Health on Free-Roaming Cats and the Public Health).

Britt, Robert Roy. The Odds of Dying. January 5, 2005.

Adjemian, Jennifer, et al. “Murine Typhus in Austin, Texas, USA, 2008.” Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2010: 412-417.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Toxoplasmosis. January 11, 2008.

American Association of Feline Practitioners and the Cornell Feline Health Center, Cornell University, College of Veterinary Medicine. Zoonotic Disease: What Can I Catch from My Cat? 2002

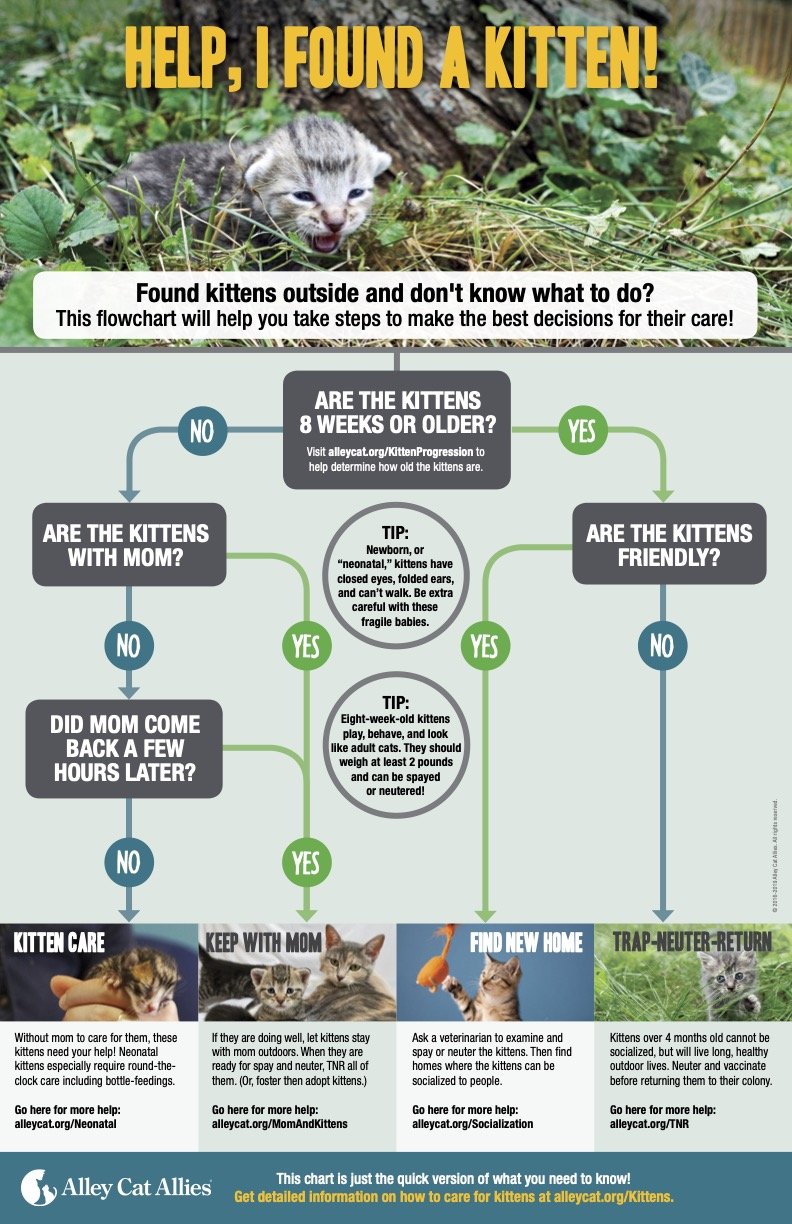

Help! I found a cat…what do I do?

Data- backed publications supporting TNR

Spehar, D. D., & Wolf, P. J. (2018). The Impact of an Integrated Program of Return-to-Field and Targeted Trap-Neuter-Return on Feline Intake and Euthanasia at a Municipal Animal Shelter. Animals, 8(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8040055

Luzardo, O. P., Vara-Rascón, M., Dufau, A., Infante, E., & Travieso-Aja, M. d. M. (2025). Four Years of Promising Trap–Neuter–Return (TNR) in Córdoba, Spain: A Scalable Model for Urban Feline Management. Animals, 15(4), 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani15040482

Hamilton F (2019) Implementing Nonlethal Solutions for Free-Roaming Cat Management in a County in the Southeastern United States. Front. Vet. Sci. 6:259. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2019.00259

Edinboro, C. H., Watson, H. N., & Fairbrother, A. (2016). Association between a shelter-neuter-return program and cat health at a large municipal animal shelter. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 248(3), 298-308. Retrieved Dec 4, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.248.3.298

Hughes, K. L., & Slater, M. R. (2002). Implementation of a Feral Cat Management Program on a University Campus. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 5(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327604JAWS0501_2

Hughes KL, Slater MR, Haller L. The effects of implementing a feral cat spay/neuter program in a Florida county animal control service. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2002;5(4):285-98. doi: 10.1207/S15327604JAWS0504_03. PMID: 16221079.

Data-backed publications supporting inefficacy of “catch and kill”

Zaunbrecher, K.L., D.V.M., & Smith, R.E., D.V.M., M.P.H. (1993). “Neutering of feral cats as an alternative to eradication programs.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 203(3), 449-452.

Mahlow, J.C., & Slater, M.R. (1996). “Current issues in the control of stray and feral cats.” Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 209 (12),2016-2020.

Jones, C. (2012). “Cats: San Jose shelter spays, releases strays.” SFGATE. Retrieved April 28, 2020 from http://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Cats-San-Jose-shelter-spays-releases-strays-2437677.php

Ji, W., Sarre, S. D., Aitken, N., Hankin, R.K.S., & Clout, M.N. (2001). “Sex-biased dispersal and a density-independent mating system in the Australian brushtail possum, as revealed by minisatelite DNA profiling.” Molecular Ecology, 10, 1527-1537.